'Inhumane': Immigration enforcement targets noncriminal immigrants from all walks of life

Story and photos by LEE ANN ANDERSON and LORENZO GOMEZ

This report is part of “Upheaval Across America,” an examination of immigration enforcement under the second Trump administration produced by Carnegie-Knight News21. For more stories, visit www.upheaval.news21.com. Tropic Press is reprinting this with their permission.

JACKSONVILLE — When Juan and Madison Pestana went on their first date in 2023, Juan vowed to always keep a bouquet of fresh flowers on the kitchen table. For nearly two years, he did exactly that.

Their love story was a whirlwind: She was an introverted medical student who grew up in Wendell, North Carolina, and he was a charismatic construction business owner from Caracas, Venezuela.

When they first met at a sushi bar, Madison didn’t expect much. That changed when she found herself in her car at 2 a.m., still talking the night away.

“He is literally my best friend … (and) the only person I’ve ever thought truly understood me as a person,” she said. “He truly is the love of my life.”

Since that first date, the Pestanas hadn’t spent more than six days apart – until immigration agents showed up outside their Miami apartment.

On May 9, the day of Madison’s graduation from medical school, Juan was taken into custody despite having no criminal record. Madison said he was tackled to the ground – a sight so jarring, she said, that a neighbor called the front office to report a potential kidnapping.

“That shouldn’t be the word that people are using when proper law enforcement is taking people into proper custody,” Madison said.

Juan has been in detention ever since. Immigration authorities say he is in the country unlawfully. His wife, an American citizen, says he unknowingly overstayed his visa after the couple used an unscrupulous notary to file his green card application.

Madison has since moved, on her own, to Jacksonville, where she started a surgical residency in July. She lives alone, works 90-hour weeks and drives more than 300 miles to and from a detention center in Broward County every weekend to visit her husband.

They’re not allowed to embrace more than twice during each visit.

“I am living my worst nightmare,” Madison said, adding what she believes Americans need to know: “What’s happening right now is not justice. This is just inhumane.”

Madison acknowledges that she once was a supporter of President Donald Trump, enticed by the idea he would remove criminals from the country. Now, she said, “I feel lied to.”

“What was promised was that we were going to make things safer for people. Do you think they’re making my life safer?” she said. “My life is immensely more dangerous now that you’ve taken my husband from me.”

‘All immigrants are being heavily scrutinized’

On the campaign trail, Trump, indeed, promised safety and security. He promised that changes to immigration policy would target criminals. His campaign, he said, was intended to rid the country of people he has called murderers, terrorists, drug dealers, animals– “the worst they have in every country, all over the world.”

When he won a second term as president, some of his supporters were immigrants themselves.

Today, some 60,000 people are being held in immigration detention – a 51% increase since January, according to the nonprofit Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse.

About 70% of those detained have no criminal record, TRAC says. Many others have convictions for offenses as minor as a traffic violation.

“Even though a lot of the rhetoric was ‘Let’s get the criminals out of the U.S.,’ that’s not actually what’s happening,” said New York immigration lawyer Pouyan Darian. “What’s happening is, all immigrants are being heavily scrutinized.”

The result, advocates argue, is an unprecedented attack on immigrants from all walks of life and living in the U.S. under all kinds of circumstances.

The administration has terminated Temporary Protected Status for hundreds of thousands of people who fled dictatorships and disasters in their home countries and were legally welcomed into the U.S. Some of these migrants – who face the loss of work visas and eventual deportation – have lived in the country for decades and have citizen spouses or children.

Before courts issued an injunction, Trump officials revoked hundreds of visas for immigrant students over noncriminal protest activities, previously dismissed misdemeanors and even traffic tickets.

Trump issued an executive order denying citizenship to anyone born on American soil to women either in the country illegally or here legally under a visa, if the father is not a U.S. citizen or green card holder. That order is on hold, for now, due to legal challenges.

The administration also wants to vastly expand its power to denaturalize those who have become U.S. citizens and give the Department of Justice discretion to pursue cases “as it determines appropriate.”

For immigrant communities across the country, the result is a climate of fear where even legal compliance offers no guarantee of protection.

In one example, Harvard University cancer researcher Kseniia Petrova, a Russian citizen, was apprehended in February at Boston Logan International Airport after she failed to declare frog embryos she’d brought into the country for research.

Although a fine and forfeiture of the undeclared item is a typical penalty in such cases, the government canceled Petrova’s visa and held her in detention for four months. She has since been indicted on smuggling charges and is out on bail as the case proceeds.

In another case, 18-year-old Guatemalan Ernesto Manuel-Andres was detained just weeks after his high school graduation during a June 4 raid at his apartment complex in Bowling Green, Kentucky.

Ernesto Manuel-Andres, an 18-year-old from Guatemala, was detained a few weeks after his high school graduation. (Photo courtesy of GoFundMe)

According to Luma Mufleh, founder of the educational nonprofit Fugees Family, Manuel-Andres is in the U.S. under “special immigrant juvenile” status, which is granted to children who have been abused, neglected or abandoned.

Beginning in 2022, immigrants with that status were protected from deportation until a visa became available. On June 6, the Trump administration rescinded that protection.

During his 20 days of detention, Manuel-Andres was transferred to three different facilities in two states. He was released June 24 on bond, and his case is still pending.

“I feel like they’re testing the limits of the law – they’re trying to see who they can take in,” Mufleh said. “And I’m like, ‘You’re going after kids? That’s who we’re going after now?’”

She described Manuel-Andres as someone who “always does the right thing without anyone asking him to do it. He’s someone you want on your team.”

There have been other instances, too.

Wualner Sauceda, a middle school teacher in Hialeah, Florida, was deported to Honduras after being detained at a regular immigration check-in as he explored a legal pathway to stay in the country.

Wualner Sauceda, a middle school teacher in Hialeah, Florida, was detained in January and deported the following month. (Photo courtesy of Wualner Sauceda)

Cliona Ward, a green card holder from Ireland who has lived for 30 years in Santa Cruz, California, was detained for more than two weeks over old drug possession charges that had been expunged. She has since been released.

Such arrests have become less predictable, with individuals being detained at court hearings or scheduled Immigration and Customs Enforcement check-ins.

“This really just forces people into the shadows – that is what the consequence is of these policies,” said Laila Ayub, an immigration attorney and co-founder of Project ANAR, an Afghan immigration justice organization.

“It’s very clear that the goal is to make things harder, to discourage people from coming here and to increase fear in our communities.”

‘My father deserves to be here’

In the small Florida town of Wimauma, southeast of Tampa, the Ambrocio family is reeling from the ramifications of the administration’s policies.

Maurilio Amizael Ambrocio, the family’s patriarch, is an evangelical Christian pastor who since 2018 had led the small congregation of Iglesia de Santidad Vida Nueva, a tight-knit group bound by shared experiences of immigration and culture.

“He’s not only our father, but he’s also our pastor, a spiritual leader for us,” said his daughter, Ashley, one of Ambrocio’s five children, who range in age from 12 to 20 and are all American citizens.

Ambrocio and his faith offered many the missing piece for which they were searching in their lives.

“He supported and helped me move forward,” said Jennifer Dominguez, a 42-year-old from Mexico who has attended Ambrocio’s church for about four years. “There was a time I didn’t want to live, and he helped me through it.”

At 15, Ambrocio left everything he knew to escape a gang trying to recruit young boys in his hometown of Cuilco, Guatemala. He initially entered the U.S. illegally, via the Arizona-Mexico border. While in the country, he’d work odd jobs to get by.

He was deported in 2006 but returned to the U.S. later that year. And although he was under an immigration removal order – issued after he was cited for driving without a license – he had a stay that had allowed him to remain in the country, his family said.

For nearly 10 years, Ambrocio regularly attended ICE check-ins without a problem. That all changed in April, when he was detained at one of those appointments while Ashley, her brother Derlin and a fellow pastor waited outside.

An immigration agent called the family back and said Ambrocio would be held for 45 hours, Ashley said. In that time, Ambrocio was taken to Glades County Detention Center.

“I was really, really scared,” Ashley said. “I don’t know how the process is. I was like, ‘What if he gets deported right there?’”

Ashley remembers the change in her mother upon hearing the news: “She looked just lonely. Her eyes were just different … like if they took something away from her – and they did.”

Weeks went by, and on June 28, the family got a call that planted a seed of hope: Ambrocio mistakenly believed he would be released while the immigration process played out. Instead, he was transferred to a staging facility in Louisiana.

A few days later, wanting to escape long-term detention, Ambrocio chose to self–deport. On July 2, he was on a plane back to Guatemala. He has been preaching at churches near his hometown of Cuilco and wants to open a tortilla business to keep himself afloat.

Ashley and Derlin have since gone to Guatemala to visit their father. When they got off the plane, they ran to him and embraced, the tears flowing.

Ashley Ambrocio and her brother, Derlin, embrace their father on Tuesday, July 8, 2025, in Guatemala City. (Video courtesy of Ashley Ambrocio)

They brought him clothing, family photos, a drawing from one of his congregants and a Bible, and together they spent time seeing places their father hadn’t seen since he was a boy.

“It felt so nice seeing him act like a child, getting excited seeing everything and taking pictures,” Ashley said. “It brings us comfort knowing he’s not suffering (in detention). He’s doing better.”

When Ashley turns 21 next July, she said, she will try to sponsor her father’s return to the United States. In the meantime, she, her mother and her four brothers are left to go on without him.

The family spends their Saturdays preparing for Sunday church services ; another pastor fills in for Ambrocio in his absence. And day and night, Ashley’s mother prays for her husband to be back in her arms.

“My father deserves to be here,” Ashley said. “Coming here for a better future isn’t a crime.”

A world on fire

Juan Pestana also had hopes of a better future when he came to the U.S. in 2021. He filed for asylum, obtained a work permit and launched a construction business – designing and building fences and pergolas.

He and Madison met two years later. Within five weeks, they were engaged. Three months after their first date, they were married.

“Never did I have any doubts about it,” Madison said of their swift courtship. “We didn’t even apply for a green card through marriage until way later.”

That’s when they got into trouble, she said.

Last fall, the couple decided to submit paperwork to get Juan his green card. They hired the same person who had filed Juan’s asylum paperwork, paying about $5,000. But in April, Madison learned the application had been denied because it was completed incorrectly. She refiled everything on her own. Juan, nevertheless, was detained the next month.

Many detainees, like Juan, were in the middle of adjusting their status, caught up in a system riddled with scams and a court backlog of more than 3 million cases – with more than 500,000 of those in Florida, statistics show.

“We tried to do this the legal way. We tried to get help so that we didn’t have a problem. We tried,” Madison said. “People need to know that this could happen to their husbands or their wives. This is not just criminals.”

On a Saturday in June, Madison made the four-and-a-half-hour drive to Broward Transitional Center for her weekly visit with Juan. Sitting in the car in the detention center parking lot, she speedily applied her makeup even as her mother, who had joined her, reminded her Juan wouldn’t care what she looked like.

Guards at the front informed visitors of the dress code: no open-toed shoes, no shorts, no sleeveless shirts. Strangers exchanged shoes, even if it meant wearing a pair four sizes too big.

Inside, detainees sat on one side of long, cafeteria-style tables, while visitors sat on the other – forcing them to maintain distance. Whenever they could, Madison and Juan squeezed hands, shared a wink and mouthed, “I love you.” Each life update was followed with tears, muddling Madison’s makeup.

She drove back that same day, arriving at the Jacksonville home Juan has yet to see for himself. They had decided to upgrade from their one-bedroom, one-bathroom apartment in Miami to a two-story house for more space, but Madison said it feels empty without Juan.

“I’m just stuck here in this big, empty house, alone,” she said, “and it just feels like there’s no way out.”

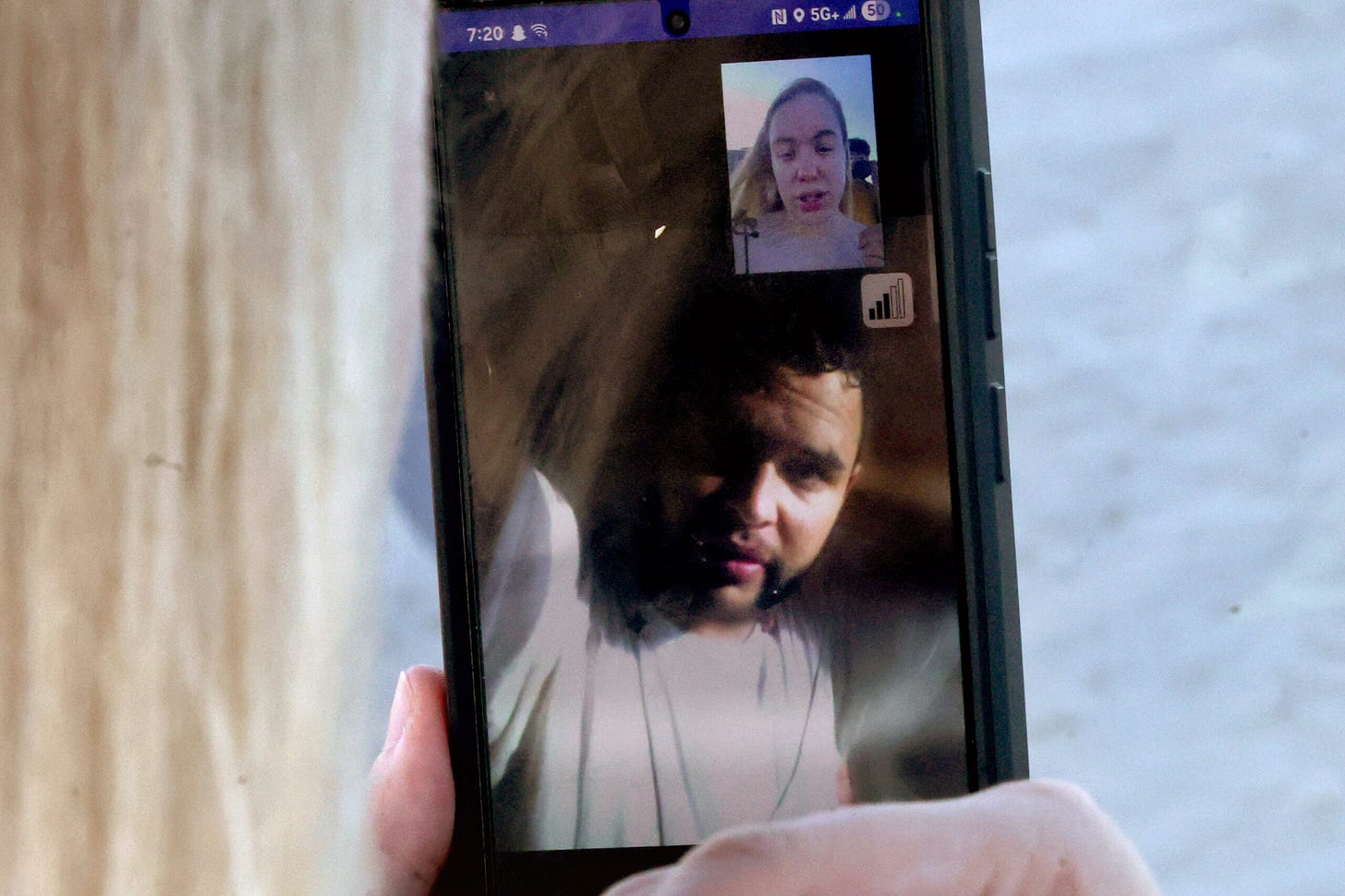

Now, while Madison works tirelessly for her surgical residency, Juan awaits a decision about his future in the country. They talk on the phone whenever Madison gets a break.

Their wish is simple: to continue the life they were building together.

“I made my life here,” Juan said in a phone interview with News21. “I met my wife, and I want to stay because we have a family here.”

“I made this country mine already.”

If Juan isn’t granted permission to remain in the U.S., he plans to self-deport to Portugal because he fears being persecuted in Venezuela. Madison then would have to decide whether to follow the love of her life, or stay behind to complete the training to which she’s dedicated years.

For the Pestanas, the consequences are personal and debilitating: the absence of a hand to hold, the silence at a dinner table once marked by fresh flowers. Madison even sleeps with Juan’s shirt on his pillow, spraying it with his cologne to remind her of his presence.

“You wake up in the morning, and for a minute, you don’t remember,” she said. “You think that everything’s OK, and then, all of a sudden, it slaps you in the face again and you remember that your whole life is upside down.

“I feel like the world is on fire outside, and all I want is my husband to walk through it with me.”

Today, some 60,000 people are being held in immigration detention – a 51% increase since January. About 70% of those detained have no criminal record. Others have already been deported or are living in hiding in the U.S., fearful of what might come. These are their stories:

Maria Bonilla

“Even though she doesn’t have the proper documentation, in my eyes, I think she’s a U.S. citizen by heart.”

Magali Bonilla

Daughter of Maria Bonilla

From left, Araceli Bonilla, Magali Bonilla, Maria Bonilla, Henrin Bonilla and Tatiana Bonilla pose for a picture. Maria Bonilla was detained in May and deported to El Salvador the next month. (Photo courtesy of GoFundMe)

In 2001, Maria Bonilla, then 17, left behind the only parents she ever knew — her grandparents — and migrated to the United States from her home in El Salvador.

Since then, she said, she feels like she hasn’t lived — only survived.

“I decided to leave for the United States because I suffered so much when I was little,” she said. “We didn’t have anything to eat, I had to work all day, and the pay was very little. … When I arrived, I arrived alone and survived.”

Now a single mother of four, Bonilla struggled to find a steady home. She lived in several apartments and houses, and sometimes stayed with friends, before settling into her own home in Gainesville, Georgia.

In 2014, she obtained a work permit, which led to higher wages. She put in overtime at a chicken plant and sometimes held two jobs at once. But she didn’t allow her children to work — she wanted them to study instead.

“She looked really worn down the past few years,” one of Bonilla’s daughters, Magali, said. “So that’s when we started to step up and work a little harder and get jobs.”

Like so many other immigrants, Bonilla had for years checked in regularly with immigration agents. But in May, she was detained at one such check-in — because her passport was missing from her paperwork, Magali said.

Bonilla was deported in June, leaving behind daughters Magali and Araceli, both in their 20s; a third daughter, 15; and an 18-year-old son.

Now, the eldest daughters have put their lives on hold to support their younger siblings. Magali dropped out of nursing school to work full time as a medical assistant, and Araceli works as a certified nursing assistant.

Magali said she has been diagnosed with depression and anxiety, which have worsened since her mother’s deportation.

Usha Tummala-Narra, a clinical psychologist specializing in immigration and trauma, says when older siblings take on the responsibilities of their parents, it can be difficult for them to process grief and bounce back emotionally.

“It’s a compounding kind of stress and trauma and a great deal of responsibility that those older siblings feel towards the younger ones,” Tummala-Narra said. “And so they end up not only dealing with their own grief, but helping siblings with their grief, and oftentimes not having enough support to be able to do that.”

Magali stressed that her mother, who is back in El Salvador now, is not a criminal —and that although she never became a U.S. citizen, she did “what U.S. citizens are supposed to do.”

“Even though she doesn’t have the proper documentation,” Magali said, “in my eyes, I think she’s a U.S. citizen by heart.”

Annette and Carlos

“I feel like nowadays it’s not like before, where there was empathy and sympathy for things.”

Carlos

Unauthorized Immigrant

Annette lives with multiple chronic illnesses and depends on her husband, Carlos, for care. Carlos moved to the U.S. from Durango, Mexico, when he was 6 and does not have legal status. (Photo by Nicole Macias Garibay/News21)

In a small apartment in Avondale, Arizona, 43-year-old Annette spends most of her days indoors, creating lifestyle videos for TikTok, visiting with family and monitoring her health. She lives with her husband of 18 years, Carlos, 42, who doubles as her caregiver.

Annette has a number of chronic illnesses, including chronic migraines, mast cell activation syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a painful connective tissue disorder. She also has diabetes and periodic paralysis.

As a result, Carlos took on the roles of breadwinner and caregiver. As a supportive and loving husband, Annette said, he did so without a second thought. He worked odd jobs; his favorite was as an auto detailer. But now, the couple face another obstacle that weighs heavily on their minds: his immigration status.

Carlos moved to Arizona from Durango, Mexico, when he was 6 years old, so his legal status was never something the couple gave much thought to. But in December 2020, Annette decided to petition for a green card for Carlos through marriage. The couple is still in the midst of the process, she said, and their anxiety has reached a tipping point, given the Trump administration’s mass deportation policies. They asked that their last name not be used because of concerns it could harm Carlos’ chance at gaining legal status.

In July, Annette obtained a letter from her doctor seeking expedited legal status for Carlos on humanitarian grounds, saying he is “essential not only for critical emotional and psychological support but also for regular medical assistance and physical care.”

Annette said she doesn’t know how she would go on if Carlos were deported.

“If something did happen, would I be able to survive that traumatic, life-changing event?” she said. “It’s not just about my chronic illness; it’s about my love for him. He’s all I know. We only know each other.

“Even when he pushes my wheelchair, he’ll be telling me, ‘You smell like an angel.’”

Currently, the two live solely off Annette’s disability check. She is unable to work because of her conditions, and Carlos is avoiding employment outside of the home because of recent upticks in immigration enforcement.

Said Carlos: “I feel like nowadays it’s not like before, where there was empathy and sympathy for things.”

Ernesto Manuel-Andres

“Ernesto always does the right thing without anyone asking him to do it. He’s someone you want on your team.”

Luma Mufleh

CEO of Fugees Family

Ernesto Manuel-Andres, an 18-year-old from Guatemala, was detained a few weeks after his high school graduation, even though he was in the country under “special immigrant juvenile” status. (Photo courtesy of GoFundMe)

Luma Mufleh, founder of an educational nonprofit that provides resources to immigrants, was on vacation in June when she got a text from a colleague: “One of the students has been detained.”

The CEO of Fugees Family learned that 18-year-old Ernesto Manuel-Andres had been caught up in the Trump administration’s immigration enforcement actions. Mufleh thought it had to be a mistake.

Originally from Guatemala, Manuel-Andres migrated to Bowling Green, Kentucky. Mufleh’s organization helped him apply for and receive “special immigrant juvenile” status, which may be granted to immigrants under 21 who’ve been abused, abandoned or neglected.

Manuel-Andres graduated from high school in May. Three weeks later, immigration agents detained him.

According to Mufleh, agents were sent to apprehend another immigrant, but when they came across Manuel-Andres, they took him in, too — even though he tried to show them his status documents.

Manuel-Andres’ status allowed him to stay in the country legally, under deferred action, as he waited for a visa. However, in June, the Department of Homeland Security changed its policy to rescind such protections.

In Bowling Green, several hundred supporters took to the streets to protest Manuel-Andres’ detention. The community also raised more than $30,000 to help with legal fees.

During his 20 days of detention, Manuel-Andres was transferred to three different facilities in two states. He was released June 24 on $1,500 bond, and his case is still pending.

“Ernesto always does the right thing without anyone asking him to do it,” Mufleh said. “He’s someone you want on your team.”

Derrick Ozamah

“That doesn’t reflect American compassion, the American spirit, the American community.”

Derrick Ozamah

Detained Immigrant

Derrick Ozamah poses for a picture with his wife, Clara Fuentes. A graduate of the University of Arizona, Ozamah came to the U.S. in 2016 from Lagos, Nigeria, to study. He was detained in June. (Photo courtesy of GoFundMe)

Derrick Ozamah came to the U.S. in 2016 from Lagos, Nigeria, to study at Iona University in New York. After transferring to the University of Arizona to be closer to family, he earned a bachelor’s degree in 2024 and soon found work as an environmental health technician for the city of Minneapolis.

He met and married Clara Fuentes, and the two returned to Arizona earlier this year to start their lives together. Instead, in June, Ozamah was detained by immigration agents, accused of overstaying his visa.

For nearly two months, Ozamah, who has no criminal record, was held in detention in Florence, Arizona. He described the conditions as “deplorable” and said he got food poisoning three times.

“If most Americans saw what’s going on in there, that wouldn’t exist,” Ozamah said. “That doesn’t reflect American compassion, the American spirit, the American community.”

Ozamah was released on bond July 27 and is awaiting his next court hearing. He and his wife said they have filed for an adjustment of status.

“It’s honestly just scary, especially now, with everything going on,” Fuentes said. “Even though … I’m remaining optimistic with this whole court system, you just never know.”

When Ozamah’s best friend, Luis De La Cruz of Phoenix, heard about the incident, he was dumbfounded. “He is the epitome of making the community better,” De La Cruz said, recalling the time Ozamah helped design a house for one of his friends’ parents in Zimbabwe.

“He’s always trying to make the people around him better,” De La Cruz added. “He’s just here to better everyone around him and be an asset.”

Wualner Sauceda

“He believes that God is taking care of him and guiding him … and that he’s going to figure his way out through this.”

Karla Hernández-Mats

Friend of Wualner Sauceda

Wualner Sauceda, a middle school teacher in Hialeah, Florida, was detained in January and deported the following month. (Photo courtesy of Wualner Sauceda)

Wualner Sauceda always knew he wanted to give back to his community in Hialeah, Florida. That’s why the 24-year-old decided to become a middle school teacher, according to his friend Karla Hernández-Mats, past president of United Teachers of Dade.

Sauceda knew his community well, and his teaching approach was informed by the problems he encountered as a teen growing up in the area. Eager students who wanted to receive a decent education faced barriers, including their socioeconomic background and immigration status.

“He understood the plight of those kids, of that community,” Hernández-Mats said. “He connected with them really, really well.”

Sauceda migrated to the United States with his cousin when they were 13 to escape violence in Honduras. After high school, he won a college scholarship for students without legal status. He obtained a degree in chemistry from Florida International University and landed a job at Palm Springs Middle School in Hialeah a month later.

Sauceda had been teaching for about a year when he was detained in January. He was deported about a month later.

Hernández-Mats said Sauceda had applied for asylum but was denied. He attended regular immigration check-ins while he explored other avenues for legal status, and it was at one of those check-ins that he was detained.

He called his uncle and asked him to break the news to his family.

“He was still trying to protect his family the best way he could, and he didn’t feel like he was in the best emotional condition to make that call and for them to feel like he was going to be OK,” Hernández-Mats said.

Back in Honduras, Sauceda has returned to a life of dirt roads, spotty Wi-Fi, a dismal job market and countryside living, Hernández-Mats said.

“He is having to adjust,” she said. “I know that because he has a strong faith that has actually kept him very serene and sane through this whole process. He believes that God is taking care of him and guiding him … and that he’s going to figure his way out through this.”

News21 reporter Hannah Psalma Ramirez contributed to this story.

Lee Ann Anderson is a senior majoring in journalism with an outside concentration in African American studies at the University of Florida. She has worked as a reporter for Fresh Take Florida, covering politics and court cases across the state. She worked as a radio journalist and photographer for WUFT News, UF’s PBS affiliate network, and as a criminal justice and breaking news reporter for The Independent Florida Alligator. She also served as a photography intern for the Florida Gators.

Lorenzo Gomez is a master’s student at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication. He holds bachelor’s degrees in political science and psychology and has experience working as a policy analyst in the nonprofit sector. His work includes helping to establish Flagstaff, Arizona’s first Indigenous cultural center. His work as a writer and photographer focuses on Indigenous communities, borderlands and culture. In 2025, he traveled to Panamá to report on global migration through the Cronkite Borderlands Project.

Isn't this supposed to be the country with a heart and soul - This is a country made up of immigrants from all over the world. Trump is a bloody fascist. Why are people bowing to that psychopath. Cowards. Cowards. The man is a whore - a narcissistic, psychopathic whore who's sold his soul to evil.

Actually had people tell me "I did it legal, so they should too" ... couldn't talk them out of voting for Trump ... wonder what they think now that doing it legal doesn't matter?